Research.The World Health Organization recommends a "see and treat" approach for improving cancer management in low-income communities. We develop biomedical devices to "see" disease with optical devices and "treat" disease in the same clinical encounter with ablative therapies. |

Current Research at the University of MarylandI. Ethanol Ablation to Treat Cervical Pre-Cancer

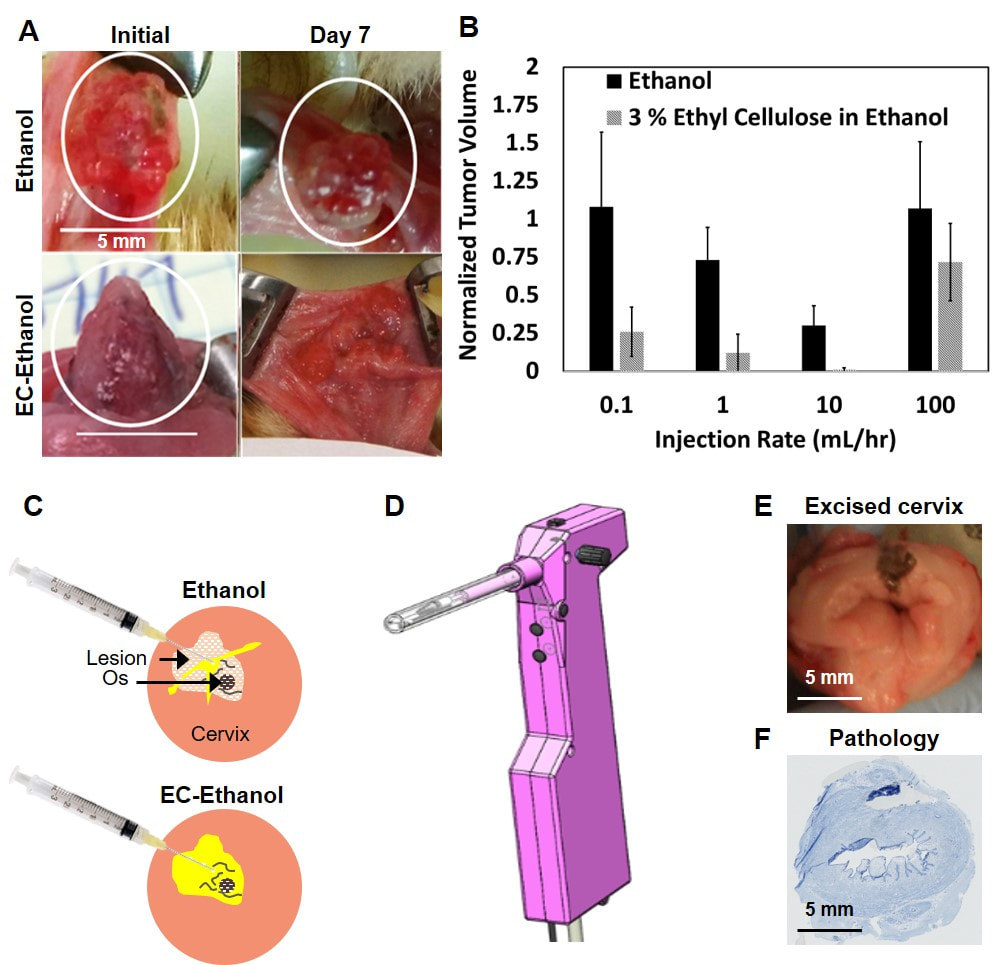

Cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death for women worldwide; 85% of deaths occur in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), despite the fact that well-established interventions exist for pre-invasive disease. A significant barrier to cervical cancer prevention in LMICs is reliable access to treatment. Cryotherapy, an ablative method in which compressed gas and a metal probe are used to freeze lesions, is recommended by the World Health Organization for use in LMICs. However, cryotherapy requires a continuous supply of pressurized liquid nitrogen, which is difficult to transport and not reliably accessible. Consequently, 80% of women diagnosed with pre-cancerous lesions in the cervix do not return for follow-up care, which contributes to high mortality rates. Ethanol ablation, which involves the injection of ethanol into diseased tissue to induce cell death, could address this need as it is portable, accessible in LMICs, and has previously been used to kill cells through chemical ablation. However, the efficacy of ethanol ablation is limited due to a propensity to leak into areas adjacent to the lesion. To reduce leakage and improve retention in the lesion, we increased the viscosity of ethanol by adding ethyl cellulose (EC) to ethanol. We initially tested the efficacy of EC-ethanol ablation in a hamster cheek pouch model of squamous cell carcinoma. We found that EC forms a gel when injected into tissue, which provides prolonged contact with ethanol, leading to localized treatment within the lesion. Our results showed that tumor volume was significantly lower for animals treated with EC-ethanol compared to ethanol alone (Panel A). Additionally, we found that reducing the infusion rate of EC-ethanol delivery from a manual injection (approximately 100 mL/hr) to 10 mL/hr decreased backflow and resulted in complete regression of all tumors treated with EC-ethanol within 7 days (Panel B). We are currently investigating the interacting effects of various delivery parameters associated with the injection and the resulting distribution volume in the cervix (Panel C). These experiments are guiding design of an injection device (Panel D) to ablate the zone needed to treat 99% of cervical pre-cancers, as defined by previous studies. The injection device will be tested in pig cervices (Panel E) to compare the volume of necrosis (Panel F) induced by EC-ethanol ablation compared to cryotherapy. This work will lead to an EC-ethanol procedure whose safety and efficacy are validated in a large animal model, which will establish the groundwork for clinical translation to women with cervical pre-cancer in LMICs. |

|

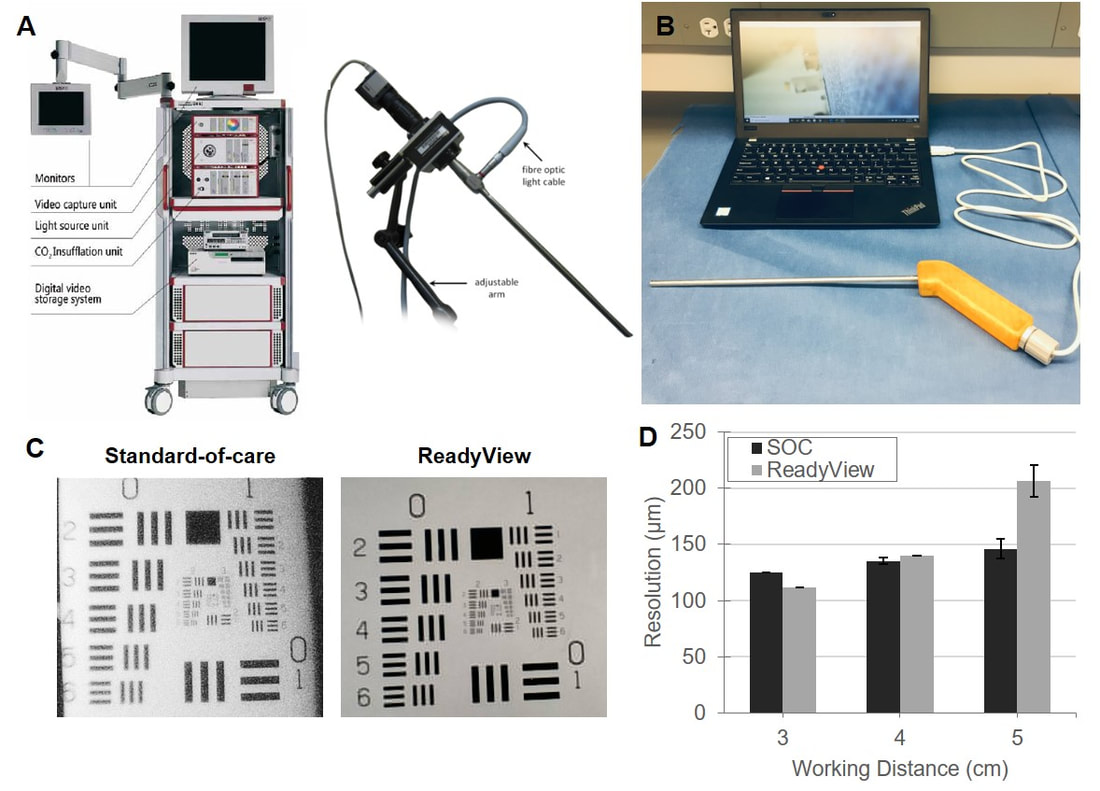

II. Affordable Laparoscopy for Laparoscopic Surgery in LMICs Laparoscopic surgery is the standard-of-care in high-income countries for many cancer excisions in the chest and abdomen. It avoids large incisions by using a tiny camera and fine instruments manipulated through keyhole incisions but is generally unavailable in LMICs aside from limited tertiary centers. Each operating room requires an expensive laparoscopic camera, viewing monitors, and related equipment (~$215,000 for initial purchase in each room, Panel A). Current technology uses fragile fiber optic cables that require constant repair, necessitating expensive service contracts. Patients in LMICs would benefit from laparoscopic surgery, as advantages include smaller incisions, decreased pain, improved recovery time, fewer post-surgical infections, and shorter hospital stays. We are developing a low-cost, durable, and reusable laparoscope called the ReadyView laparoscope for use in LMICs. Rather than having an expensive light source and camera coupled to a fragile fiber optics, the ReadyView laparoscope prototype (Panel B) contains a color complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) detector and ring of LEDs that has been moved to the front of the device. This enables a significant decrease in cost and complexity (cost of goods = $120) while also maintaining the image quality (Panel C) and resolution (Panel D) of a standard-of-care (SOC) laparoscope. Additionally, images can be displayed on a laptop computer, obviating the need for expensive monitors and cables and preventing loss of function during power-outages. We are currently optimizing the design of the ReadyView laparoscope and will evaluate its performance and safety through bench testing and animal testing. We will work with an industry partner to develop a commercial prototype and purse key studies required for regulatory clearance. |

Previous Research at Duke University |

|

I. Pocket Colposcope to Diagnose Cervical Pre-Cancer

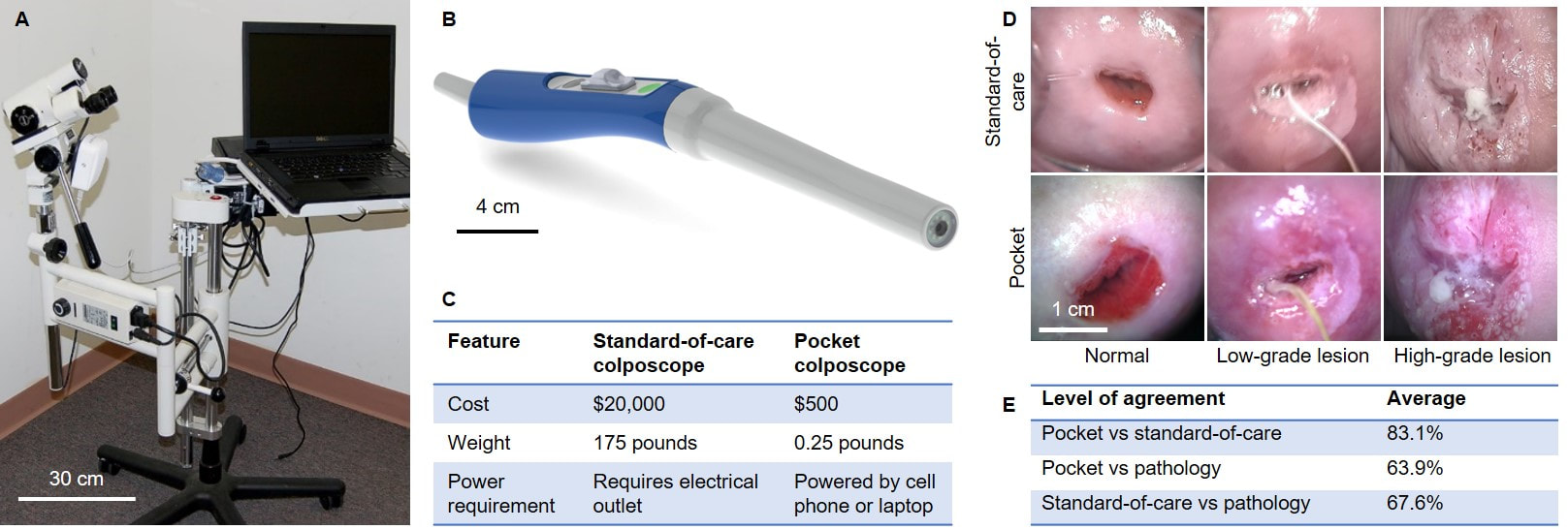

While there is considerable effort to make human papillomavirus (HPV) testing more widely available as a primary screening tool in LMICs, only a small percentage of women who are HPV positive have lesions that require treatment. Thus, the ultimate bottleneck is the colposcopy exam, which entails visualization of the cervix using a low-power microscope called a colposcope to determine if a lesion is present. Colposcopy is problematic in LMICs because many primary health facilities lack expensive colposcopes (Panel A), requiring women to travel to tertiary facilities for a follow up exam. To address this shortcoming, we developed the Pocket colposcope (Panel B), which enables a secondary screen (visualization of the cervix) to be performed during the same clinical encounter as primary screen (HPV testing). Unlike to the standard-of-care colposcope, the Pocket colposcope device is low-cost, portable, and interfaces with a phone or computer (Panel C). The Pocket colposcope is being used in clinical investigations in the U.S., Perú, Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia to show equivalence to a standard-of-care colposcope (Panel D). In one of the latest studies of 200 patients in Perú, expert physician interpretation agreed 83.1% of the time between the two devices (Panel E). When compared to pathology, physicians achieved an accuracy of 63.9% for the Pocket and 67.6% for the standard-of-care colposcope. These results indicated that the Pocket colposcope performs similarly to the standard-of-care colposcope when used to identify pre-cancerous lesions during colposcopy exams. |

|

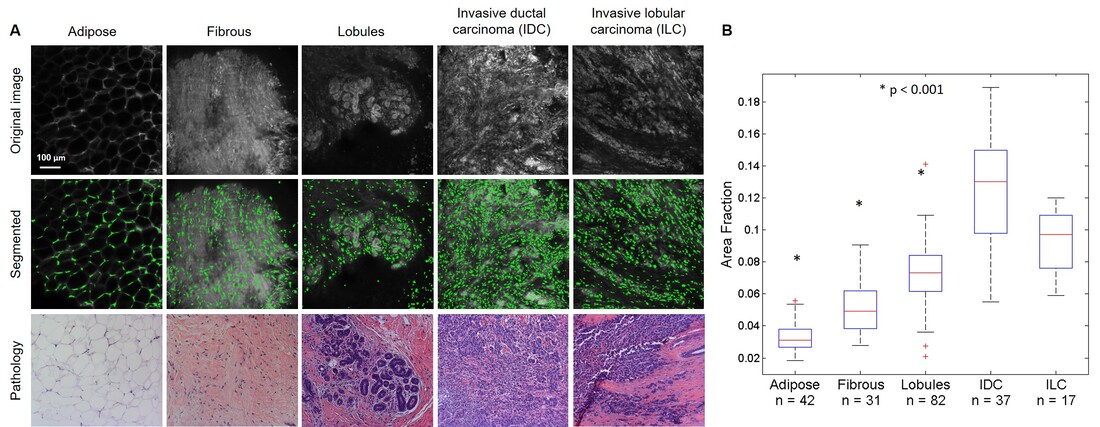

II. Micro-Anatomical Quantitative Imaging to Diagnosis of Thick Tissues at the Point of Care Histopathology is the clinical standard for tissue diagnosis. However, histopathology has several limitations including that it requires tissue processing, which can take 30 minutes or more, and requires a highly trained pathologist to diagnose the tissue. Additionally, the diagnosis is qualitative, and the lack of quantitation leads to possible observer-specific diagnosis. Several clinical situations could benefit from more rapid and automated histological processing, which could reduce the time and the number of steps required between obtaining a fresh tissue specimen and rendering a diagnosis. For example, there is need for rapid detection of residual cancer on the surface of tumor resection specimens during excisional surgeries, which is known as intraoperative tumor margin assessment. Additionally, rapid assessment of biopsy specimens at the point-of-care could enable clinicians to confirm that a suspicious lesion is successfully sampled, thus preventing an unnecessary repeat biopsy procedure. Rapid, low-cost histological processing could also be potentially useful in settings lacking the human resources and equipment necessary to perform standard histologic assessment. Lastly, automated interpretation of tissue samples could potentially reduce inter-observer error, particularly in the diagnosis of borderline lesions. To address these needs, we developed optical systems and automated algorithms to diagnose tumor margins intra-operatively to improve the accuracy of cancer excision and reduce the likelihood that the patient needs to return for a re-excision surgery. We used a high resolution microendoscope (HRME) in combination with a topical fluorescent contrast agent acriflavine to image preclinical sarcoma tumor margins. Acriflavine localizes to the nuclei of cells, but also shows some affinity for collagen and muscle. We developed a method that could differentiate nuclei from background tissue and enable automated diagnosis of sarcoma tumor margins. A computational technique called sparse component analysis (SCA) was adapted to isolate nuclei from muscle and adipose tissue. Differences in nuclear density and size were correctly identified with SCA in a cohort of ex vivo images and were used to develop a multivariate model to differentiate between positive and negative in vivo sarcoma margins, demonstrating the diagnostic potential of our approach. This combination of tools was also used to detect the presence of malignancy in clinical core needle breast biopsies. We built a structured illumination microscope (SIM) to increase the field of view and implement optical sectioning, which greatly improved image contrast and enabled surveying larger regions of clinical tumor margins. We used an algorithm called maximally stable extremal regions (MSER) for nuclear segmentation in SIM images and compared MSER and SCA by applying both algorithms to a series of preclinical sarcoma images acquired with the HRME, SIM, and a confocal microscope. Results indicated that MSER was the most versatile algorithm across multiple microscopy systems, which was further confirmed by using MSER to successfully segment nuclei in confocal microscopy images of human breast tissue (Panel A), which could be used to calculate features, such as area fraction (the total nuclear area divided by the total area), that could differentiate between malignant and benign tissue types (Panel B). |